Varieties of the Utopian Fredric Jameson

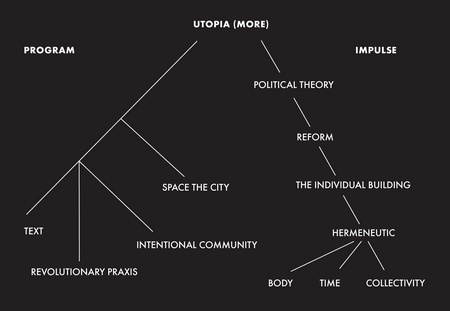

It has often been observed that we need to distinguish between the utopian form and the utopian wish: between the written text or genre and something like a utopian impulse detectable in daily life and its practices by a specialized hermeneutic or interpretive method. Why not add political practice to this list, inasmuch as whole social movements have tried to realize a utopian vision, communities have been founded and revolutions waged in its name, and since, as we have just seen, the term itself is once again current in present-day discursive struggles? At any rate, the futility of definitions can be measured by the way in which they exclude whole areas of the preliminary inventory.1

In this case, however, the inventory has a convenient and indispensable starting point: it is, of course, the inaugural text of Thomas More (1571), almost exactly contemporaneous with most of the innovations that have seemed to define modernity (conquest of the New World, Machiavelli and modern politics, Ariosto and modern literature, Luther and modern consciousness, printing and the modern public sphere). Two related genres have had similar miraculous births: the historical novel, with Waverly in 1814, and Science Fiction (whether one dates that from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in the same years [1818] or Wells’ The Time Machine in 1895).

Such generic starting points are always somehow included and aufgehoben in later developments, and not least in the well-known shift in utopias from space to time, from the account of exotic travelers to the experiences of visitors to the future. But what uniquely characterizes this genre is its explicit intertextuality: few other literary forms have so brazenly affirmed themselves as argument and counterargument. Few others have so openly required cross-reference and debate within each new variant: who can read Morris without Bellamy? Or indeed Bellamy without Morris? So it is that the individual text carries with it a whole tradition, reconstructed and modified with each new addition, and threatening to become a mere cipher within an immense hyperorganism, like Stapleton’s minded swarm of sentient being.

Yet the lifework of Ernst Bloch is there to remind us that utopia is a good deal more than the sum of its individual texts. Bloch posits a utopian impulse governing everything future-oriented in life and culture—and encompassing everything from games to patent medicines, from myths to mass entertainment, from iconography to technology, from architecture to eros, from tourism to jokes and the unconscious. Wayne Hudson expertly summarizes his magnum opus as follows:

“In The Principle of Hope Bloch provides an unprecedented survey of human wish pictures and daydreams of a better life. The book begins with little daydreams (part I), followed by an exposition of Bloch’s theory of anticipatory consciousness (part II). In part III Bloch applies his utopian hermeneutics to the wish pictures found in the mirror of ordinary life: to the utopian aura which surrounds a new dress, advertisements, beautiful masks, illustrated magazines, the costumes of the Ku Klux Klan, the festive excess of the annual market and the circus, fairy tales and colportage, the mythology and literature of travel, antique furniture, ruins and museums, and the utopian imagination present in dance, pantomime, the cinema and the theater. In part IV Bloch turns to the problem of the construction of a world adequate to hope and to various ‘outlines of a better world.’ He provides a 400-page analysis of medical, social, technical, architectural, and geographical utopias, followed by an analysis of wish landscapes in painting, opera, and poetry; utopian perspectives in the philosophies of Plato, Leibniz, Spinoza, and Kant, and the utopianism implicit in movements agitating for peace and leisure. Finally, in part V Bloch turns to wish pictures of the fulfilled moment which reveal ‘identity’ to be the fundamental supposition of anticipatory consciousness. Once again, the sweep is breathtaking as Bloch ranges over happy and dangerous experiences in ordinary life; the problem of the antinomy between the individual and the community; the problem of the antinomy between the individual and the community; the works of the young Goethe, Don Giovanni, Faust, Don Quixote, the plays of Shakespeare; morality and intensity in music; hope pictures against death, and man’s increasing self-injection into the content of religious mystery.”2

We will return to Bloch shortly; but it should already be clear that his work raises a hermeneutic problem. Bloch’s interpretive principle is most effective when it reveals the operation of the utopian impulse in unsuspected places, where it is concealed or repressed. But what becomes, in that case, of deliberate and fully self-conscious utopian programs as such? Are they also to be taken as unconscious expressions of something even deeper and more primordial? And what becomes of the interpretive process itself and Bloch’s own philosophy of the future, which presumably no longer needs such decoding or reinterpretation? Yet the utopian exegete is not often herself the designer of utopias, and no utopian program bears Bloch’s own name.3 There is here at work the same hermeneutic paradox Freud confronted when, searching for precursors of his dream analysis, he finally identified one obscure aboriginal tribe for whom all dreams had sexual meanings—except for overtly sexual dreams as such, which meant something else.

We would therefore do better to posit two distinct lines of descendency from More’s inaugural text: the one intent on the realization of the utopian program, the other an obscure yet omnipresent utopian impulse finding its way to the surface in a variety of covert expressions and practices. The first of these lines will be systemic, and will include revolutionary political practice, when it aims at founding a whole new society, alongside written exercises in the literary genre. Systemic will also be those self-called intentional communities; but also the attempts to project new spatial totalities, in the aesthetic of the city itself.

The other line of descent is more obscure and more various, as befits a protean investment in a host of suspicious and equivocal matters: liberal reforms and commercial pipe dreams, the deceptive yet tempting swindles of the here and now, where utopia serves as the mere lure and bait for ideology (hope being after all also the principle of the cruelest confidence games and of hucksterism as a fine art). Still, perhaps a few of the more obvious forms can be identified: political and social theory, for example, even when—especially when—it aims at realism and at the eschewal of everything utopian as well as piecemeal social democratic and “liberal” reforms, when they are merely allegorical of a wholesale transformation of the social totality. And as we have identified the city itself as a fundamental form of the utopian image (along with the shape of the village as it reflects the cosmos),4 perhaps we should make a place for the individual building as a space of utopian investment, that monumental part which cannot be the whole and yet attempts to express it. Such examples suggest that it may be well to think of the utopian impulse and its hermeneutic in terms of allegory: in that case, we will wish in a moment to reorganize Bloch’s work into three distinct levels of utopian content: the body, time, and collectivity.

Yet the distinction between the two lines threatens to revive the old and much-contested philosophical aim of discriminating between the authentic and the inauthentic, even where it aims in fact to reveal the deeper authenticity of the inauthentic as such. Does it not tend to revive that ancient Platonic idealism of the true and false desire, the true and false pleasure, genuine satisfaction of happiness and the illusory kind? And this at a time when we are more inclined to believe in illusion than in truth in the first place.5 As I tend to sympathize with this last, more postmodern, position, and also wish to avoid a rhetoric which opposes the reflexive or self-conscious to its unreflexive opposite number, I prefer to stage the distinction in more spatial terms. In that case, the properly utopian program or realization will involve a commitment to closure (and thereby to totality): was it not Roland Barthes who observed, of Sade’s utopianism, that “here as elsewhere it is closure which enables the existence of system, which is to say, of the imagination?”6

But this is a premise that is not without all kinds of momentous consequences. In More, to be sure, closure is achieved by that great trench the founder causes to be dug between the island and the mainland and which alone allows it to become utopia in the first place. A radical secession further underscored by the Machiavellian ruthlessness of utopian foreign policy which—with its bribery, assassination, mercenaries, and other forms of Realpolitik—rebukes all Christian notions of universal brotherhood and natural law and decrees the foundational difference between them and us, foe and friend, in a peremptory manner worthy of Carl Schmitt and characteristic in one way or another of all subsequent utopias intent on survival within a world not yet converted to Bellamy’s world state: as witness the sad fate of Huxley’s Island or the precautions that are required by situations as different as Skinner’s Walden communities or Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars.7

Totality is then precisely this combination of closure and system in the name of autonomy and self-sufficiency and which is ultimately the source of that otherness or radical, even alien, difference already mentioned above and to which we will return at some length. Yet it is precisely this category of totality that presides over the forms of utopian realization: the utopian city, the utopian revolution, the utopian commune or village, and of course the utopian text itself, in all its radical and unacceptable difference from the more lawful and aesthetically satisfying literary genres.

Just as clearly, then, it will be this very impress of the form and category of totality which is virtually by definition lacking in the multiple forms invested by Bloch’s utopian impulse. Here we have rather to do with an allegorical process in which various utopian figures seep into the daily life of things and people and afford an incremental, and often unconscious, bonus of pleasure unrelated to their functional value of official satisfactions. The hermeneutic procedure is therefore a two‑step method, in which, in a first moment, fragments of experience betray the presence of symbolic figures—beauty, wholeness, energy, perfection—which are only themselves subsequently to be identified as the forms whereby an essentially utopian desire can be transmitted. It will be noted that in this Bloch often appeals to classical aesthetic categories (which are themselves ultimately theological ones as well), and to that degree his hermeneutic may also be grasped as some final form of German idealist aesthetics as it exhausts itself in the late 20th century and in modernism. Bloch had far richer and more varied tastes than Lukács, and attempted to accommodate popular and archaic culture, modernist as well as realist and neoclassical texts, into his utopian aesthetics: but the latter is perfectly capable of assimilating postmodern and non-European, mass-cultural tastes, and this is why I have proposed to reorganize his immense compendium in a new and tripartite way (body, time, and collectivity) which corresponds more closely to the levels of contemporary allegory.

Materialism is already omnipresent in an attention to the body which seeks to correct any idealism or spiritualism lingering in this system. Utopian corporeality is, however, also a haunting which invests even the most subordinate and shamefaced products of everyday life, such as aspirins, laxatives, and deodorants, organ transplants, and plastic surgery, all harboring muted promises of a transfigured body. Bloch’s reading of these utopian supplements—the doses of utopian excess carefully measured out in all our commodities and sewn like a red thread through our practices of consumption, whether sober an utilitarian or frenzied-addictive—now rejoins Northrop Frye’s Blakean myths of eternal bodies projected against the sky. Meanwhile, the overtones of immortality that accompany these images seem to move us urgently onward the temporal level, becoming truly utopian only in those communities of the preternaturally long-lived,8 as in Shaw’s Back to Methusaleh, or the immortal, as in Boorman’s film Zardoz (1974), significantly offering fodder for the antiutopians in the accompanying deterioration of the utopian vision: the suicidal tedium of Shaw’s long-lived elders, the sexless ennui of the inhabitants of Zardoz’s Vortex. Meanwhile, liberal politics incorporates portions of this particular impulse in political platforms offering enhanced medical research and universal health coverage, although the appeal to eternal youth finds a more appropriate place on the secret agenda of the right and the wealthy and privileged, in fantasies about the traffic in organs and the technological possibilities of rejuvenation therapy. Corporeal transcendence then also finds rich possibilities in the realm of space, from the streets of daily life and the rooms of dwelling and work place, to the greater locus of the city as in ancient times it reflected the physical cosmos itself.

But the temporal life of the body already resituates the utopian impulse in what is Bloch’s central concern as a philosopher—namely, the blindness of all traditional philosophy to the future and its unique dimensions, and the denunciation of philosophies and ideologies, like Platonic anamnesis, stubbornly fixated on the past, on childhood and origins.9 It is a polemical commitment he shares with existential philosophers in particular, and perhaps more with Sartre, for whom the future is praxis and the project, than with Heidegger, for whom the future is the promise of mortality and authentic death; and it separates him decisively from Marcuse, whose utopian system drew significantly, not merely on Plato, but fully as much on Proust (and Freud), to make a fundamental point about the memory of happiness and the traces of utopian gratification that survive on into a fallen present and provide it with a “standing reserve” of personal and political energy.10

But it is worth pointing out that at some point discussions of temporality always bifurcate into the two paths of existential experience (in which questions of memory seem to predominate) and of historical time, with its urgent interrogations of the future. I will argue that it is precisely in utopia that these two dimensions are seamlessly reunited and that existential time is taken up into a historical time which is paradoxically also the end of time, the end of history. But it is not necessary to think of this conflation of individual and collective time in terms of any eclipse of subjectivity, although the loss of (bourgeois) individuality is certainly one of the great antiutopian themes. But ethical depersonalization has been an ideal in any number of religions and in much of philosophy as well; while the transcendence of individual life has found rather different representations in science fiction, where it often functions as a readjustment of individual biology to the incomparably longer temporal rhythms of history itself. Thus, the extended life spans of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars colonists allow them to coincide more tangibly with long-term historical evolutions, while the device of reincarnation in his alternate history Years of Rice and Salt affords the possibility of reentering the stream of history and development over and over again.11 Yet a third way in which individual and collective time come to be identified with each other is in the very experience of everyday life, according to Roland Barthes the quintessential sign of utopian representation: “la marque de l’Utopie, c’est le quotidien.”12 Where biographical time and the dynamics of history diverge, this day-by-day life in successive instants allows the existential to fold back into the space of the collective, at least in utopia, where death is measured off in generations rather than in biological individuals.

Stapleton’s traveler, meanwhile, lives time in an indeterminable Einsteinian relativity, but also combines with a host of other individuals and their temporalities in a collective experience for which we have no ready-made linguistic or figurative categories. It is an account worth quoting in its own right, and marks the way in which a temporal investment of the utopian impulse moves toward that final form which is the figure of the collectivity as such:

“It must not be supposed that this strange mental community blotted out the personalities of the individual explorers. Human speech has no accurate terms to describe our peculiar relationship. It would be as untrue to say that we had lost our individuality, or were dissolved in a communal individuality, as to say that we were all the while distinct individuals. Though the pronoun ‘I’ now applied to us all collectively, the pronoun ‘we’ also applied to us. In one respect, namely unity of consciousness, we were indeed a single experiencing individual; yet at the same time we were in a very important and delightful manner distinct from one another. Though there was only a single, communal ‘I,’ there was also, so to speak, a manifold and variegated ‘us,’ an observed company of very diverse personalities, each of whom expressed creatively his own unique contribution to the whole enterprise of cosmic exploration, while all were bound together in a tissue of subtle personal relationships.”

At this point the expression of the utopian impulse has come as close to the surface of reality as it can without turning into a conscious utopian project and passing over into that other line of development we have called the utopian program and utopian realization. The earlier stages of utopian investment were still locked into the limits of individual experience, which is not to say that the category of collectivity is unbounded either—we have already hinted at its structural requirement of closure, to which we will return later on.

For the moment, however, it suffices to observe that, short of any conscious utopian politics, the collective knows a variety of negative expressions whose dangers are very different from those of individual egotism and privilege. Narcissism characterizes both, no doubt; but it is collective narcissism that is most readily identified in the various xenophobic or racist group practices, all of which have their utopian impulsion, as I have notoriously tried to explain elsewhere.13 Bloch’s hermeneutic is not designed to excuse these deformed utopian impulses, but rather entertains a political wager that their energies can be appropriated by the process of unmasking, and released by consciousness in a manner analogous to the Freudian cure (or the Lacanian restructuring of desire). This may well be a dangerous and misguided hope; but we leave it behind us when we pass back over into the process of conscious utopian construction again.

The levels of utopian allegory, of the investments of the utopian impulse, can therefore be represented thus:

THE COLLECTIVE (anagogical)

TEMPORALITY (moral)

THE BODY (allegorical)

UTOPIAN INVESTMENT (the text)

Note

1 / But see, for an authoritative statement, Lyman Tower Sargent, “The Three Faces of Utopianism,” Minnesota Review 7.3 (1967), p. 222–230 and “The Three Faces of Utopianism Revisited,” utopian studies 5.1 (1994), p. 1–37. As utopian studies are a relatively recent disciplinary field, bibliographies of theoretical interventions in it are still relatively rare: but see those in Tom Moylan, Demand the Impossible, Methuen, New York 1986; and Barbara Goodwin and Keith Taylor, The Politics of Utopia, Hutchinson, London 1982. The journal Utopian Studies can be consulted for recent developments in this area. Theoretical contributions to the study of science fiction are another matter: see Veronica Hollinger’s splendid overview, “Contemporary Trends in Science Fiction Criticism, 1980–1990,” Science Fiction Studies 78 (1999), p. 232–262, and for a more Francophone perspective, the bibliography in Richard Saint-Gelais, ĽEmpire du pseudo, Nota bene, Quebec City 1999. For both, of course, we are fortunate to be able to draw on the superb Encyclopedia of Science Fiction of John Clute and Peter Nicholls, Martin’s Griffin, New York 1995; and for utopias, on the Dictionary of Literary Utopias of Vita Fortunati and Raymond Treason, Champion, Paris 2000.

2 / Wayne Hudson, The Marxist Philosophy of Ernst Bloch, St Martin’s Press, New York 1982, p. 107. We must also note Ruth Levites’ critiques of the notion of a utopian “impulse” in her Concept of Utopia, Syracuse University Press, Syracuse 1990, p. 181–183. This book, central to the constitution of utopian studies as a field in its own right, argues for a structural pluralism in which, according to the social constructions of desire in specific historical periods, the three components of form, content, and function are combined in distinct and historically unique ways: “The main functions identified are compensation, criticism, and change. Compensation is a feature of abstract, ‘bad’ utopia for Bloch, of all utopia for Marx and Engels and of ideology for Mannheim. Criticism is the main element in Goodwin’s definition. Change is crucial for Mannheim, Bauman, and Bloch. Utopia may also function as the expression of education of desire, as for Bloch, Morton, and Thompson, or to produce estrangement, as for Moylan and Suvin. If we define utopia in terms of [only] one of these functions we can neither describe nor explain the variation” (p. 180).

3 / Tom Moylan pertinently reminds me that Bloch already had a concrete utopia; it was called the Soviet Union.

4 / See Claude Lévi-Strauss, “Do Dual Organizations Exist?” Structural Anthropology I, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1983; and Pierre Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1977.

5 / See Gilles Deleuze, Cinéma II: L’Image-temps, Minuit, Paris 1985, chapter VI, on “le faux”; and also Jean-Paul Sartre, Saint Genet, Pantheon, New York 1983, on “le toc,” 358ff.

6 / Roland Barthes, Sade, Fourier, Loyola, Seuil, Paris 1971, p. 23.

7 / And we might have added the historical tragedy of Winstanley and St George’s Hill (along with the fate of Goetz’s utopian commune in Sartre, Le Diable et le bon dieu: it is true that this last is imposed rather than intentional, which was presumably the other point the philosopher of freedom and praxis wanted to make). As is well known, Huxley’s late work, Island (1962), represents his attempt to rectify the satiric Brave New World of 1932 with the construction of a “serious” (although narrative) contribution to the utopian genre. B.F. Skinner (1904–1990), one of the more idiosyncratic American theorists of behaviorism and the inventor of the so-called Skinner box, wrote a major utopia in Walden Two (1948), in which (in my opinion) “negative conditioning” plays little part: Kim Stanley Robinson (1952–) is the author of not one, but two Utopian cycles, the so-called Orange County trilogy (1984–1990) and the Mars trilogy (1992–1996), with a third one, centering on ecological disaster and its utopian possibilities, on the way.

8 / See Fredric Jameson, Longevity as Class Struggle, Verso, London and New York 2005, part two, essay 7.

9 / See Ernst Bloch’s attack on anamnesis in The Principle of Hope, The MIT Press, Cambridge 1986, p. 18.

10 / Herbert Marcuse, Eros and Civilization, chapter 11, Random House, New York 1962, p. 18.

11 / Years of Rice and Salt (2002) offers the chronicle of a world from which Europe and Christianity have been eliminated by the Black Death in the 14th century AD, a world in which a “native America” high civilization flourishes in the Western hemisphere and China an Islam have become the major subjects of a history that concludes with equivalents of “our” First World War, “our” revolutionary 1960s, and (hopefully) a different kind of future from our own.

12 / Roland Barthes, Sade, Fourier, Loyola, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1997, p. 23.

13 / See the Conclusion to my The Political Unconscious: Narrative as Socially Symbolic Act, Cornell University Press, Ithaca 1981, and also my review article “On ‘Cultural studies,’” Social Text 34 (1993), p. 17–52.

Source

Fredric Jameson, Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fiction, Verso, London and New York 2005, p. 1–9.